France

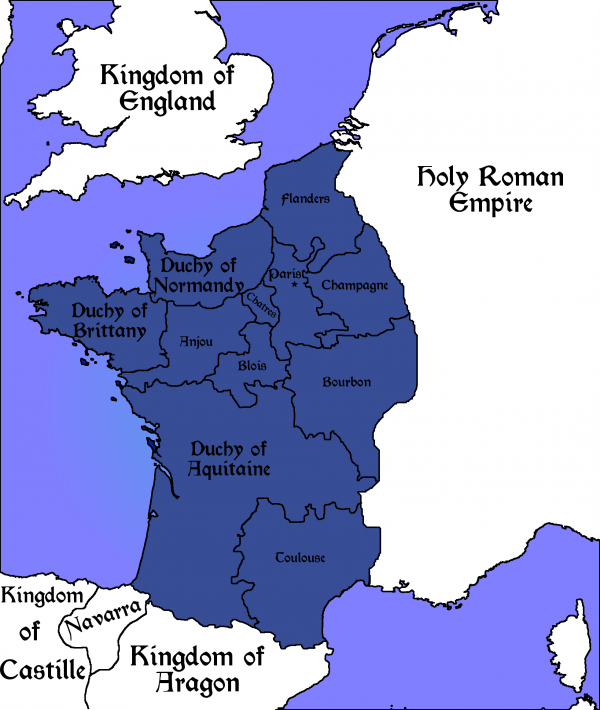

It's complicated. Firstly, about a quarter to a third of the France we know (the most eastern bits) are part of the Holy Roman Empire. Secondly, although the king is technically the overlord of the entire country, he only directly controls a very small area (Paris and roughly the equivalent of the modern Parisian suburbs). The rest are held by lords, counts, and dukes—the equivalent of the unruly barons of England, and if they are not as contumacious as the English barons, it can easily be argued that they are even more self-centered and less concerned with “their” nation as a whole.

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the Aquitaine.

Recent History

(for Charlemagne to the present, please see main history page)

The history of the last fifty years or so is entirely tangled up in the personalities of the ruling dynasties of France and England: the Capets and the Plantagenets. The Capets, by and large, are quiet, studious, and introspective. The Plantagenets are passionate, witty, strong, charismatic, good-looking, and a lot more personable.

Eleanor of Aquitaine inherited a rich, culturally thriving duchy which was approximately a third of France's land mass. She was beautiful, intelligent, learned. When she became duchess in her teens, she was immediately seen as the most eligible and desirable woman in the kingdom.

She married the king, Louis, but it did not go well. She had the marriage annulled—divorce does not exist—because of consanguinity; then married Henry, to whom she was even more closely related.

Philip Augustus inherited his father's envy and thus dislike. It did not help that, by and large, Henry and Eleanor's children inherited both their parents' charisma and personality, and Philip Augustus his father's. When in his teenage years, Philip got ill and lost all his hair and his finger and toenails, making him even less unprepossessing, things deteriorated further, especially since Richard Lionheart was everything Philip was not, including handsome and incredibly popular (even in France).

In the last two or three years, however, there has been somewhat of a rapprochement. Henry and Eleanor's son Geoffrey, duke of Brittany, and Philip have become very close. It is said that when Geoffrey nearly died two years ago (some say at a tournament; some say of a knife in the ribs), it was Philip himself who carried him into the shrine of Ste. Genoveve, and whose prayers to the saint healed him.

The inability of either Louis or Philip to contain their fractious vassals has led some people to remember, conveniently, that the Capetians were originally elected monarchs, and to seek for the true descendants of Charlemagne. Others hold that the Geoffrey/Philip relationship is the way forward and possibly the way to unite the two kingdoms for the greater glory of France.

Politics

The duchies of France are currently Brittany, Aquitaine, and Normandy. All are held by the Plantagenets, either by right or by marriage. The most important counties are Flanders, Champagne, Toulouse, Anjou, Bourbon, Blois, and Chartres. They hold them, in theory, from the King of France, Philip Augustus. In practice, they do not even bend the knee in ceremonies, and pay only perfunctory taxes, preferring instead to run their own regions (which governmentally are mostly autonomous and not dependent on Paris) and courts. About two-thirds of modern France are part of the Angevin Empire. One of the reasons France is so comparatively poor is that the incomes from these vast regions go to support the English crown, and not the French.

The countess and regent of Champagne is Marie, elder daughter of Eleanor and Louis. She has her mother's looks and wit, and hates her half-brother Philip, who attempted to steal/annex part of her land and marry her off (she is a widow) to someone she abhorred. She refused. It is rumoured that you could hear the argument in Rome. She is extremely loyal to her mother, and very fond of her other half-brother Richard Lionheart.

The countess and regent of Blois is Alix, younger daughter of Eleanor and Louis. She, too, is a widow, and after his dealings with Marie Philip left Alix alone in the matter of remarriage. Alix is very fond of her half-sister Alais, countess of a particularly tricky bit of Normandy, who is engaged to Richard Lionheart.

The count of Toulouse, Raymond, is Languedoc born and bred, a good friend of Eleanor of Aquitaine's and Marie de Champagne's, and doesn't give a damn about northern France, which he sees as boorish, saved only by the contributions of the fey. He is on good terms with the Spanish kingdoms—all of them, including Andalusia—and presides over one of the most cultured and culturally rich societies in the world. They also don't care much one way or the other for the church, so as well as orders like the Cistercians, heresies, such as the Cathars, are often able to put down roots in Occitania.

Aquitaine is fanatically loyal to its duchess. They are also very fond of her son Richard, her daughter Marie de Champagne, and her daughter Eleanor of Castile. They are not fond of Geoffrey, whom they find to be less than up-front about his dealings.

With such little support and lacking the personal charisma to generate any, the only way the kings of France have been able to go forward is with the support of the Church and its allies (including the fey).

On the other hand, there have been no real, concerted land wars in France this century, so the common folk are generally unmoved by political machinations. That said, there is no upwards mobility—indeed, you're tied to the land unless you take stock to city markets or have the freedom as a monk or nun to travel between chapter houses—unless you have the looks, intelligence or talent to come to the notice of a patron who is higher in society than you are.

Society

Culture

Northern France has grandeur. It has inspired the beginnings of what will be come to be known as the Gothic movement, and the great cathedral-building has started. The Abbey of St Denis is rich beyond imagining, in all senses of the word. The Cluniac monasteries are beautiful. Law has proliferated; the study of it, philosophy, and theology have resulted in the founding of the University of Paris, one of the best in the world. If grandeur and opulence is what you want—if showing how closely the Church and France's hearts are knit together—then there is no better place than Paris. Fey of knowledge and those who love grand ceremony (which is a great many of them, and all of them beautiful) flock there.

Northern France has grandeur. It has inspired the beginnings of what will be come to be known as the Gothic movement, and the great cathedral-building has started. The Abbey of St Denis is rich beyond imagining, in all senses of the word. The Cluniac monasteries are beautiful. Law has proliferated; the study of it, philosophy, and theology have resulted in the founding of the University of Paris, one of the best in the world. If grandeur and opulence is what you want—if showing how closely the Church and France's hearts are knit together—then there is no better place than Paris. Fey of knowledge and those who love grand ceremony (which is a great many of them, and all of them beautiful) flock there.

Marie de Champagne has sponsored such notables as Chrétien de Troyes and Andreas Capellanus, the author of the great Arthurian romances (the subject matter of which, it is said, was dictated and possibly conceived of by the countess herself) and the new book The Art of Courtly Love, which is selling like a 12th-century equivalent of the Harry Potter or 50 Shades phenomena, despite being in Latin, as well as encouraging the development of the troubadour “movement” in the north. Under initially, the influence of Queen Eleanor, and now her daughter in Champagne, the north has learned that manners are an art form, and to be like the court—courtois, or courteous, is now something desirable, no matter what rank you are.

But the sun in northern France, say some, is anaemic as its heart. The grandeur masks an emptiness of true spirit. Occitania has passion, warmth, tolerance, a zest for life that is alien to the king and his ilk. There is a difference between splendour and doing things splendidly–Languedoc does the latter.

Occitania promotes the arts in a really big way. Having a large bit of hospitable Mediterranean coast, its traders are numerous, and its influences (incoming and outgoing, physical and metaphorical) cosmopolitan.

Aquitaine spans both north and south, and exemplifies both. Its court at Poitiers has seen both troubadours and courtly love, developed both to high art forms, and sent them back out into the world again. Aquitaine is mostly on good terms with the Church; the fey are welcome (and soak up the atmosphere). In short, in terms of both cultural and political importance, Eleanor of Aquitaine is the most important woman in Europe—which is obviously why only she could unite it in a crusade.

Courtly Love

This started informally with the troubadours in the Aquitaine and Occitania, then was developed to a high art in the courts of Champagne. At the moment, with Eleanor away on Crusade, her daughter Marie de Champagne is holding Court in Poitiers. Such is the power and practice of courtly love that these courts, nearly a year old now, are called, simply, the Courts of Love.

Anyone can be a courtly lover, no matter their station in life. To be a courtly lover you must subject yourself utterly to another, virtually worship that person with heart, soul, body. This other is almost always of higher social status—in fact the higher the better, as by aspiring to the love of a person of higher status you will inevitably better yourself, making yourself more than you were born and more worthy of your beloved's attention.

You must bring gifts to your beloved, and make sure no envious eyes or tongues can bear false witness against you to them. For this reason, love is sweetest when it is secret. (The big disjoin between “love should be a secret” and “you should write songs and stories praising your love and sing them everywhere” is only a disjoin if you are foolish enough to use your beloved's name—you must speak in general or coded terms! Your beloved, being wiser than you, will know they are meant, and you will be safe.)

It is said a trustworthy messenger can make a small fortune ferrying messages between lovers at the Court of Love. It is also said that one messenger tried to sell his knowledge and his body was found with the heart ripped out. (The heart was found, later, by an assistant pig-keeper, half-eaten in a pig trough. It was Countess Marie's favourite pig.)

The Troubadours

And so I weep both night and day

and cannot see, even in dreams

a way to cure me of this love

that gnaws and eats my heart away.

-Peirol, troubadour

The first troubadour was Guillaume IX, Duke of Aquitaine, Eleanor of Aquitaine's grandfather (as I said, impossible to overestimate the importance of the Aquitaine). Ranging from bawdy to quasi-religious, his example and patronage developed the troubadours.

The troubadours come from every walk of life, from the Countess of Dia to itinerant minstrels who wander from patron to patron earning their keep. A key thing about the troubadours' song is that they are written in the vernacular–not in Latin, and not in any fancy falutin' high sort of speech.

In practice, it can be politically perilous to, say, write love and praise to your boss' sister/brother/wife/husband/mother, and frequent changes of patrons occur, and most troubadours become itinerant once or twice in their career. However, the best troubadours are sought out by the most important people to compose songs about them, and it is said that only troubadours know what is going on in the many bedrooms of France. (In these instances it is wise to remember Countess Marie's pig.)

Troubadours, and their cousins the joglars and joglaresas (the jugglers and tumblers of Spain), often cross the Pyrenees in both directions. Eleanor of Castile has set up a court in Castile trying to rival her half-sister's; the Muslim world has cottoned on to the idea of an idealised love, feeds its songs into Eleanor's court, which then flow back into the Courts of Love. And so forth.

It is said that even in the dour Holy Roman Empire, there are minstrels calling themselves minnesinger. And if these have changed the songs to praise the Virgin as one would a beloved? Well, then, the Church is a patron too, no? Perhaps if one is forced to the inclement north of France the church will look more kindly on the voice of a troubadour if it praises God's mother. (And indeed, this is true—Philip is torn between wanting to encourage praise of the church, becoming the acknowledged king of the most Christian and most artsy court in the world, and utter, utter hatred of the influence his half-sister has gained with and over the troubadours and writers. The Church is wealthier, anyway, and winning some of the performers away.)

The Cistercians

Perhaps here it is most easily understandable what the Cistercians rebelled against. Why their churches have no ornament but the naked stone, and why Bernard of Clairvaux preached a particular kind of purity that is simply not evident even in some other sectors of the French church. The Cistercians are yearly growing in power. They build largely on land that no one wants—swamps, the tops of barren hills or mountains, and reclaim it, hard work being an offering to God. And then the community they produce spreads, or local nobles join the life of seclusion, bringing with them their land. And if we mention the Cistercians, we might as well treat of:

The Cathars

Heretics as far as the body of the Church are concerned, the Cathars consider themselves the only Christians. The movement is at least a hundred years old, and has most of its influence in Occitania, though they have started moving into Etruria and the southern reaches of the Holy Roman Empire.

Heretics as far as the body of the Church are concerned, the Cathars consider themselves the only Christians. The movement is at least a hundred years old, and has most of its influence in Occitania, though they have started moving into Etruria and the southern reaches of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Cathars are very, very successful. They do one thing the Church has never done: preach to the common folk in their own language. It has proved an incredibly powerful tool. Despite not having a priesthood as such, the Cathar leaders have met with some of the Church's best theologians and defeated them in open debate—hugely humiliating for professional preachers to be defeated by, as they saw it, heretic weavers and labourers.

Catharism is a dualist faith. The God of the New Testament is a good god, representing all that is best and brightest–namely, the spirit and the soul. The God of the Old Testament is evil and created the material world to entrap and ensnare the best of human life (its spirit and soul) in corrupt flesh. The worst thing, therefore, you can do is create another life, for by that you are dooming another spirit to years of corruption. (Whether this means total abstinence from sex or abstinence from procreative sex, with all that implies, is a point of argument.)

The Cathars have the equivalent of the laity–ordinary members who followed the tenets of the Bible as closely as they could, including the Ten Commandments, and swearing no oaths that were not to God (some suspect the originators of the faith fell afoul of some playful fey). They kept practising their usual crafts and occupations. No cloisters or abbeys for the Cathars. The biggest concern after an otherwise ordinary life was the sacrament of consolamentum or solace, which guaranteed their soul would not be reincarnated, and would instead be free to “rejoin the light.”

There are also the inner circle, the perfecti. These either took a more arduous route at conversion, receiving the rite of solace immediately, or older folk who had survived a time of trial, received the sacrament of solace, and become perfecti. They cannot kill; they cannot lie. They will not take oaths under any circumstances. (There are no known fey perfecti.)

Convents and Abbeys

The Second Lateran Council of 1139 was as much about breaking the back of the double monastery-convents as it was about asking its priests not to practice fey magic. Abbots had been marrying abbesses; their children inheriting the abbacy. This was particularly rife in France, and was one of the main movements behind the institution of celibacy of the clergy.

Monastic movements are still strong in France, and get stronger and more powerful with every third daughter and second son who decide to dedicate their lives to the church rather than family life, bringing with them this charter and that bit of land.

Commerce

If so much of the profit from France's natural and popular resources weren't going to England, France would be a lot richer. Still, Philip Augustus has grand plans to enlarge the walls of Paris, so that twice as much land is defensible. Rumour has it he is in debt to the Church from the very inception of this project. Still, masons from all over the world are flocking to Paris–and if not to Paris, than elsewhere in northern France, to help with cathedral building and other grand expansionist views that the king and church hold.

Tales of Place, of Folk and Fey

Brittany

Brittany is the northwest peninsula of France. Currently under the regency of Geoffrey, son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, for his young daughter Fair Joan. Geoffrey's ex-wife is Constance, now Countess of Richmond, who brought Brittany as her dowry to the marriage. When the Pope annulled the marriage at Constance's request (after all, an annulment had precedence with her mother-in-law Eleanor, who is said to have had a quiet word), she was dispossessed, and fled to England.

In the meantime Geoffrey has been making himself and his daughter much more popular than Constance's family had ever been, to the extent of learning the language and even going on progress—but with a small household, careful not to over-tax any of his hosts. Brittany is rich in land and land resources, and Brest is a thriving fishing village, but it has no big cities, and is relatively poor in actual wealth.

Carnac

The village of Carnac boasts the largest collection of standing stones in the world, avenue after avenue of them, henges, single menhirs, dolmens, tumuli. It is rumoured to have its own deity, Drilego, the Singer in the Stones, and the Church holds little sway here. Some say it belongs to the druids, and other that its practices stretch back even farther than that.

The Duke has been seen to pay his respects here, as other places in Brittany.

Roussillon

Skies which range from violet at night to the purest blue in the day, shockingly green trees, and earth every colour of red, yellow, and orange, Roussillon is said to be the most beautiful place in France, and the place where one end of the rainbow that God sent as his covenant after the flood touched the earth.

Skies which range from violet at night to the purest blue in the day, shockingly green trees, and earth every colour of red, yellow, and orange, Roussillon is said to be the most beautiful place in France, and the place where one end of the rainbow that God sent as his covenant after the flood touched the earth.

Eleven shades of highest-grade ochre are produced in the pits of Roussillon, and are sought for as pigments world-wide.

Poitiers

The capital of the Aquitaine. Eleanor has seen the addition of the Hall of Lost Footsteps, which is so vast even echoes die. Of course, there are those who say the room has a more sinister purpose—that the stone benches which ring the hall with its soaring wooden beams serve as some sort of summary justicial court for the fey, or some such. However, currently it is filled with the sounds of troubadours and celebrations of courtly love.

Lusignan

With the diaspora of the seelie court in the time of Charlemagne, not all fey were native to or remained on land. Mélusine, a water fey, fell in love with a prince of Poitou. She managed to change herself to a human form, but had to revert once a week. She charmed the prince, and they married, but when Mélusine's true form was revealed, she retreated, wailing, to the sea. But they had already had several children, and the house of Lusignan grew in power, being both lords and merchants with strong connections to the Holy Land and even the Empire of Islam, to the extent that Henry II of England often combatted the upstart house, who were challenging his hegemony in Anjou.

Mélusine, of course, is still alive, and it's said she sits on the rocks beneath the castle and wails at moments of importance for her line—that she warned the house about Henry's approaches, and sings at the birth of another child.

The current Lady of Lusignan, with whom Henry II had more than one run-in, is Sister Eustasia (see Law and Justice page), who styles herself Countess. Frankly, with the other trouble she causes him, the title of Countess is Philip's smallest worry where she's concerned.

Fey

Dent-de-Lion

With her mane of dark blonde hair and golden fangs, Dent-de-Lion (or just Lion) is an awesome sight, but she is as far as anyone has experienced a mild-mannered reporter architect in the service of the King of France. She loves high, soaring things, and making stone appear light.

Bertran de Born

Anything but mild-mannered, this wild, passionate fairy has devoted himself to the concept of courtly love, and has composed many of the most haunting melodies the troubadour movement has ever produced. It is rumoured he is also the person responsible for the cutting, satirical songs that are circulating in Occitania about King Philip.