Ireland

Politics

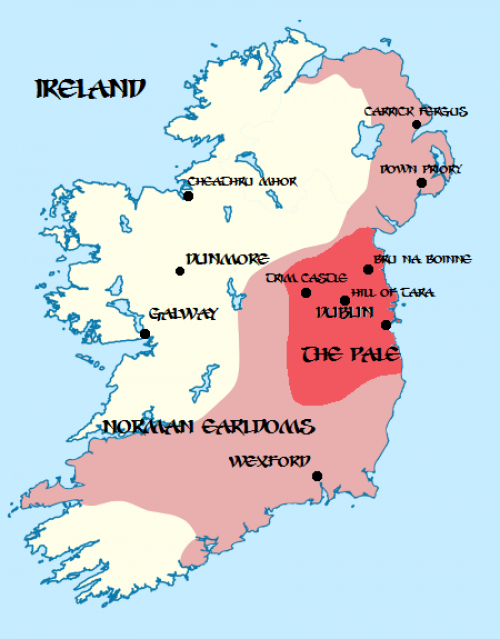

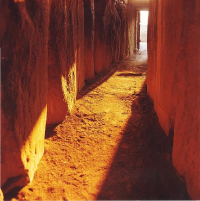

The Pale

Populated primarily by Christian English settlers, the borders of the Pale demarcate the seat of Norman control on the Island; and arguably its limit. Beyond the palisade fence from which it draws its name lies the private domains of marauding Knights and the untamed wilds of Pagan Lands; within there is a measure of security and civilisation. But with the death of Henry II the inhabitants of Dublin shelter behind their city walls and wonder how much longer their peace will last.

The Norman Earldoms

With the invasions of Robert De Clare and Henry II came dozens of Lords, complete with retinues of Knights and mercenaries. In Ireland they saw a fertile land, and one ripe for the taking by the bold and ruthless. Always acknowledging their “everlasting loyalty to the crown” but rarely doing much by way of following its orders, men such as Raymond FitzGerald and Mary de Courcy began to carve out their own petty kingdoms. It has been barely two decades since their arrival, yet already half the country has fallen beneath the steel shod hooves of Norman Cavalry. Soon, they believe, all will be theirs. Yet the speed of their advance conceals weakness at its heart; for they rule as Christians over a Pagan people, and the Druids have plans of their own.

The Irish Kingdoms

At first many of the Irish monarchs failed to realise the threat posed by the Normans, indeed many were eager to ally with Henry II. But now, with their neighbours conquered or made clients, they realise their folly. The High Monarch Carrigan Ua Conchobair is attempting to bring them together with the aid of the Druids, though some doubt whether the one who signed the Treaty of Windsor has the best interests of all Irishmen at heart. Perhaps the death of Henry presents an opportunity too fortunate to refuse, or perhaps overconfidence will be their doom, and the Pagans will perish at the point of Norman swords. Only time, and the omens of the Old Gods, can tell.

At first many of the Irish monarchs failed to realise the threat posed by the Normans, indeed many were eager to ally with Henry II. But now, with their neighbours conquered or made clients, they realise their folly. The High Monarch Carrigan Ua Conchobair is attempting to bring them together with the aid of the Druids, though some doubt whether the one who signed the Treaty of Windsor has the best interests of all Irishmen at heart. Perhaps the death of Henry presents an opportunity too fortunate to refuse, or perhaps overconfidence will be their doom, and the Pagans will perish at the point of Norman swords. Only time, and the omens of the Old Gods, can tell.

History

Ireland in Ancient Times

Like Scotland, most of Ireland remained beyond the reach of Roman conquests. In the centuries between the birth of Christ and the Invasion of the Normans, the Irish organised politically in small fiefdoms known as Tuatha, each ruler of which strove to claim the position of High Monarch, and in doing so to gain mastery over the entire island. The Greatest rivalries were those between the Monarchs of the North, the Ui Neill, and their southern foes.

The Vikings

In this divided land, where over a hundred petty monarchs contended, the Vikings saw rich pickings. First raiding parties struck the Eastern coast, attacking unprotected settlements without warning. Then the Longports were built, encampments from which the Vikings might restock their ships and launch raids against Mercia and Wales. At last whole armies were landed onshore, and Norse cities - Wexford and Dublin amongst them - were established. Though they never attempted a full conquest of the mainland, arguably thanks to the vigilance of the Ui Neill High Monarchs, the Vikings frequently embroiled themselves in the conflicts of the periods, and emerged the victors more often than not.

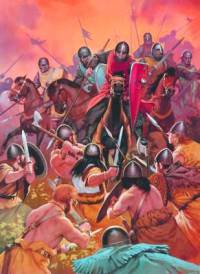

The Norman Invasion

In the early part of the current Century, Diarmait Mac Murchada faced utter ruin. She had been Lady of Leinster, a major southern province; but now her allies were slain and a large host, lead by the new High Monarch Tigernán Ua Ruairc, swept across her lands. She fled to Wales, then England. In a stroke of good fortune Henry II gave his Lords permission to join Mac Murchada in retaking her Kingdom. Chief amongst these Norman volunteers was the Marcher Lord Robert “Strongbow” De Clare. When Murchada return to Ireland, she did so at the head of an army of Norman and Welsh mercenaries, to reconquer Leinster in short order. The Normans under Strongbow captured the Viking city states of Dublin and Wexford in the process, and Norman Knights fanned out across the land, seeking new territories to conquer and subdue.

Henry II's Invasion

Worried about the potential for Strongbow to develop his own fiefdom away from Royal influence and urged on by the Pope (who had given him a Papal Bull legalising an invasion “to convert the heathen peoples”), Henry II launched his own expedition. He landed in Dublin in 1171 AD, with a large army and a still larger contingent of English settlers. Though the Irish rulers were concerned about dealings with Christians, they were more worried by the rapid expansion of the Norman knights and the rising power of Leinster, now with Mac Murchada at its head.

It was in this climate of suspicion and fear that the treaty of Windsor was signed in 1175 AD. In it the new High Monarch of Ireland, Carrigan Ua Conchobair, was given all lands outside the Royal territory of the Pale, the conquests of the Norman knights (such as De Clare) and the Kingdom of Leinster.

The Downfall of the Treaty

But a mere decade later, the treaty had fallen apart. With both Strongbow and Mac Murchada dead of natural causes and Henry back in England there was no one to control the opportunistic Norman Lords; least of all Carrigan Ua Conchobair, barely able to organise their vassals despite continuing claims of high monarchship. The Incursions of Norman Lords escalated rapidly, their territories growing into Earldoms larger than those of their English contemporaries. Most notable amongst these new Hiberno-Norman nobility were Mary de Courcy, who captured Eastern Ulster from the Pale to the North Atlantic and Raymond FitzGerald, whose territories range from Limerick to Leinster. As prince Henry's younger sister, Mary was appointed Queen of Ireland and lead an expedition to enforce his authority in 1185. However it was a notorious failure. Outside of the Pale, Mary is known as “lady” instead of Queen, possessing little power and less respect.

Society

Commerce and Culture

Geographically, Ireland is divided between low central plains and craggy coastal mountain ranges - especially around the Western coastline. Large numbers of lakes and high rainfall make it well suited to agriculture, but also heavily forested and marshy.

Geographically, Ireland is divided between low central plains and craggy coastal mountain ranges - especially around the Western coastline. Large numbers of lakes and high rainfall make it well suited to agriculture, but also heavily forested and marshy.

The majority of citizens work and live as subsistence farmers. Traditionally these farmers have operated a type of tribal sharecropping known as Doer Ceilsine; agreements by which a tenant gives his lord a portion of each years crop and a guarantee of military service in exchange for a seven year loan of land and cattle. In this economy Cows are the most important unit of exchange, providing a mobile stock of wealth that produces milk, meat, leather and horn. However in the lands under Norman rule an feudalistic system has been imposed along the lines of that practiced in England; moving away from sharecropping contracts to permanent tenancy.

In addition to farming, Ireland is home to many herdsmen, who practice transhumance, moving their flocks to higher pastures in Summer, and lower ones in winter. Ireland has a strong network of trading ports, including Dublin, Wexham and Galway.

Religion

In the millennium since the birth of Christ, missionaries have found Ireland poor soil for the seeds of their teaching. Those few who did cross the sea from France or England faced a populace wedded to the Old Gods, and Druids eager to sacrifice the acolytes of competing deities. The Norman invasion changed that; although the Popes call for Henry to convert the Irish was more excuse than purpose for the King, he brought with him English Christian settlers, and Priests eager to convert the locals. A notable feature of Irish Christianity is the lack of local saints due to the short time part of the populace has been Christian; indeed the most common worshipped here are those of Wales, which provided many of the settlers for Henrys' expedition.

In the millennium since the birth of Christ, missionaries have found Ireland poor soil for the seeds of their teaching. Those few who did cross the sea from France or England faced a populace wedded to the Old Gods, and Druids eager to sacrifice the acolytes of competing deities. The Norman invasion changed that; although the Popes call for Henry to convert the Irish was more excuse than purpose for the King, he brought with him English Christian settlers, and Priests eager to convert the locals. A notable feature of Irish Christianity is the lack of local saints due to the short time part of the populace has been Christian; indeed the most common worshipped here are those of Wales, which provided many of the settlers for Henrys' expedition.

Currently the religious situation in Ireland is unstable. The Pale is largely Christian thanks to the influx of settlers and priests. The independent Irish Kingdoms are entirely Pagan. Yet in the Norman Earldoms a pagan populace stirs beneath Christian rulers. Some attempt to impose Christian beliefs with an iron fist; tearing down henges and temples to raise crosses in their place. Others seek reconciliation, marrying with Gaelic families or even converting to the Old Gods in secret ceremonies. All the while the Druids fight a secret war with Christian Knights, attempt assassinations of missionaries and incite revolt against the Norman overlords.

There are added dimensions when the mutual support between the Irish pagans and the Inheritors of the Old Ways is considered. At present both pagan and Christian forces in both lands are divided equally resulting in a stalemate, but any event could change that: Ireland is a religious tinderbox, and Henry II's death may provide the spark.

Military

Irish warfare has traditionally focused around small hit-and-run raids, known as Crech, with the aim of stealing cattle and valuables. However with the slow agglomeration of the Tuatha and the threat of organised Norman and Viking armies, a more conventional style of warfare has developed. At the centre of any Irish army is the monarch's own retinue of lightly armoured but well trained mounted warriors (often recruited from their own kin), known as the “troops of the household”. These soldiers ride into battle bareback with lances and swords.

Accompanying these are two types of infantry. The first are light infantry called Ceithern (known as “Kern” by the Normans), who arm themselves with short spears and brightly painted shields. Often these warriors enter battle without armour, or naked save for the blue symbols of Pagan Gods. To them steel or chainmail is seen as both cumbersome and an indication of cowardice and dishonour. Ranged weapons such as bows are similarly eschewed, however Javelins are commonly used by both the “troops of the household” and the Ceithern. Ceithern were raised from two different sources; wandering mercenaries (Buanna) and levied tenant farmers. Both employ young men and women to carry their weapons onto the battlefield, in a manner similar to the squires of English aristocracy.

In recent decades a new form of heavy infantry has entered into Irish armies; armed with axes or claymores and armoured in mail. These Galloglaigh, as they are known, are primarily Scottish mercenaries, but they have increasingly been imitated by both the Irish monarchs and their Hiberno-Norman rivals. On the battlefield they act as shock troops, placed at the centre of an armies formation or as bodyguards around the general or warleader.

Notable Places

Towns

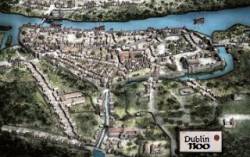

Dublin: Established as a Viking settlement and Longport in the 10th century, Dublin was one of the first settlements to fall to the Normans. As a hub of trade, shipping and craftsmanship the town has no equal in all of Ireland. It is also the most populous of Ireland's settlements, and the centre of Norman rule. The city is walled, but has no central keep.

Dublin: Established as a Viking settlement and Longport in the 10th century, Dublin was one of the first settlements to fall to the Normans. As a hub of trade, shipping and craftsmanship the town has no equal in all of Ireland. It is also the most populous of Ireland's settlements, and the centre of Norman rule. The city is walled, but has no central keep.

Wexford: Another Viking statelet subsumed by Norman conquests, Wexford was conquered by Robert Strongbow. However on his death ownership of it and its lands was transferred to Strongbow's second in command, Robert FitzGerald. It currently acts as his capital and base of operations in the Island.

Galway: A small fortified town constructed in 1124 by Carrigan Ua Conchobair's father Tordeilbach, it currently acts as a well defended harbour for the High Monarch's fleet and a potential redoubt against Norman armies.

Dunmore: A town that currently serves as Carrigan Ua Conchobair's capital and moot for other rulers.

Castles and Fortifications

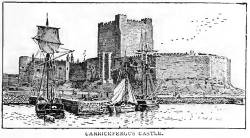

Carrick Fergus: The “Rock of Fergus” was founded in the 6th century by the local King Fergus Mor Mac Eirc. After Mary De Courcy completed her conquest of Ulster and the Eastern coast she chose this village as the site for a grand stone castle, one of the greatest in Ireland. With its tall central keep, curtain walls and seaboard position (half the castle faces out to the ocean, the other half looks down on a sheltered harbour) the stronghold is uniquely defensible.

Carrick Fergus: The “Rock of Fergus” was founded in the 6th century by the local King Fergus Mor Mac Eirc. After Mary De Courcy completed her conquest of Ulster and the Eastern coast she chose this village as the site for a grand stone castle, one of the greatest in Ireland. With its tall central keep, curtain walls and seaboard position (half the castle faces out to the ocean, the other half looks down on a sheltered harbour) the stronghold is uniquely defensible.

Trim Castle: The largest fortification in Ireland, Trim Castle was the work of Hugh De Lacy and his son Walter De Lacy; it was designed to defend the territories of the Pale for Henry II (and also, some suspect, to outdo the fortress of the De Courcy's, the De Lacy's greatest rivals). Enemies must pass through twin palisades, a deep ditch and thick stone ring walls before they can reach the keep itself. The Castle is also located next to a river, enabling transport to sea and further hindering any attack.

Holy Sites

Bru Na Boinne: Dating back tens of thousands of years before written history, and further thousands before Christianity even began, Bru Na Boinne is a sprawling and ancient complex of tombs, megaliths and henges. It is traditional for the Druids to bury the bodies of the greatest High Monarchs beneath the mounds. These rulers are buried with the wealth of their office and the bodies of their servants, as both sacrifice and commendation to the Old Gods. Much to the disgust of the Druids, the site now resides within Norman lands. However the Christians have left it well alone thus far, perhaps afraid of the Druids; perhaps of the restless and unnumbered dead.

Bru Na Boinne: Dating back tens of thousands of years before written history, and further thousands before Christianity even began, Bru Na Boinne is a sprawling and ancient complex of tombs, megaliths and henges. It is traditional for the Druids to bury the bodies of the greatest High Monarchs beneath the mounds. These rulers are buried with the wealth of their office and the bodies of their servants, as both sacrifice and commendation to the Old Gods. Much to the disgust of the Druids, the site now resides within Norman lands. However the Christians have left it well alone thus far, perhaps afraid of the Druids; perhaps of the restless and unnumbered dead.

Hill of Tara: In ancient times the Hill of Tara was the seat of the High Monarchs of Ireland, where they met with lesser monarchs to confirm their rulership in Pagan ritual - a symbolic marriage to the God Totatis that conferred upon them the right to rule. As with Bru Na Boinne, it currently lies in Norman controlled lands.

Cheathru Mhor: Centred around a great cairn, Cheathru contains multiple sunken tombs and temples to the Old Celtic Gods. With other holy sites controlled by the Normans, Cheathru Mhor is the current centre of Druidic faith and sacrifice in Ireland.

Down Priory: One of the few Christian churches outside the Pale, Down Priory (which is located in eastern Ulster) was founded in 1183 with a generous grant from Mary De Courcy. The priory is popular as a charitable institution and place of learning, but it must be protected by Norman Knights for fear of Pagan attack.

Cathedral of the Holy Trinity: A large Christian Cathedral founded by Henry II in the aftermath of his invasion. The Cathedral is the centre of Christian worship in Dublin, and by extension the rest of the Pale.

Tales of Folk and Fey

The Court of Stone

Since Charlemagne's treaty the Fae have been trapped within our world, divorced from the source of their power. Most wish to return home. Of them the members of the Court of Stone are the most fervent; Fey who eschew the human world and attempt to escape, by any means necessary. They pursue their goals with cold and unrelenting fury, and both their assumed forms and habitation reflect that purpose. The former are twisted and bizarre, melded to differ as far from the human (and that of their fellow fey) as possible. The latter is a great stone tower, craggy and monstrous; built from the thousand interlocking columns of the Giant's Causeway. It now rises impossibly high in the causeway's place, a mass of angular planes and austere grandeur. They say that when the Court of Stone find a way back to their home it will come crashing to the earth, to wake the giants from beneath the hills, and the Leviathans from under the waves.

Old Woman Willow

Of all the fey, none love living creatures more than Old Woman Willow. She moves from village to village, across wood and marsh and mountain, ministering to everything that crawls and hops and flies across the emerald earth. Her face is green as fresh shoots, her hair is a cascade of curling roses and pale willow leaves. When she angers, thorns break through the bark-brown crust of her skin. When she comes to a settlement the inhabitants welcome her with garlands of flowers and free cattle in her honour. In return she heals the sick - man and beast alike - then passes on her way. The great and good seek her for advice, for her birds see everything under the sun and make their reports faster than a man ahorse.

But there are those that fear and hate her too. Many a village has seen blood spilt whilst Woman Willow visited it - of animals or men - and had its crops rot in the fields or herds disappear overnight. Druids and Normans alike have had their hunts halted by walls of thorns, their dogs lead astray by unknown magic; Old Woman Willow, letting sacrifice or sport escape.

The Court of Faces

A more merry band of creatures is scarce to be found upon the British Isles, nor a more miserable affliction upon its wealthier inhabitants, than the Court of Faces. This troupe of Sprites, lead by a fey by the name Magnolio, appear as a band of childlike jesters, dressed in absurd and outlandish fashion. They delight in balls, feasts and celebrations (the more extravagant the better); but their greatest passion is the playing of practical jokes, most of which stray well over the line of criminality, and are amusing only to them.

Their common practise is to arrive unannounced in a nobles home (often after the declaration of some ceremony or dinner), and avail themselves of his hospitality in the most disruptive manner possible; emptying his cellars of wine and food, stealing small valuables and breaking larger ones. If permitted to act in such a manner they usually grow tired and move on after a day or so. If resisted, however, they embark upon a prolonged guerrilla campaign of “jokes” against the master of the house; often extending to sabotage, arson and kidnapping. Having menaced most countries in Europe (including England) and been expelled forcibly as a consequence, they have at last arrived in Ireland, to take a measure of the larders and treasuries of local lords.